DAY 1 / THE TRANSITION

20.7.2015 / Helsinki – Tallinn – Hara submarine docks – Rohu nuclear missile base / 187 km and ferry across the Gulf of Finland.

I was not quite there. My limbs felt sluggish and a veil swayed between perception and reaction. I had been burning the candle at both ends for too long and was now paying the price. Riding a KTM 690 Enduro R in traffic was not the smartest thing to do, but I had a ferry to catch. In fact a strange rattle from the front sprocket worried me considerably more than the possibility of a traffic accident.

The previous three days had been a blur of flying from Berlin to Helsinki, final service work on the bike and packing up. The wrenching had been an uphill battle of my own making; after putting everything together, the bike wouldn’t start. So I had torn the bike apart, gone through everything and even replaced the fuel pump and injector before realising that the spark plug lead had come off accidentally at some point. Although it was a relief to hear the bike sputter to life, my stupidity had put me behind schedule and very low on sleep and food.

Once the bike was up and running, packing the gear was a frantic last minute operation. I was due to meet two Swedish riders in Estonia a few hours later, and I didn’t want them having to sit around waiting for me. Not that the ferry would wait for me either way. Instead, it would go its merry way and I’d be left sitting on the dock, desperately trying to score a ticket for the bike and myself in the middle of the high season of the Nordic holidays.

Fortunately I pulled up to the queue of bikes, waiting to board the ferry, in time. On queue it started to rain, and I took shelter from it under a gangway. It always rained during the first day of every ride for some reason, but I was hoping for better weather on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland. My concerns with the weather soon dissipated as I mentally went through all gear and wondered if I had forgotten something. I had never left for a long ride in such a hurry, and it felt odd. Also due to the fact, that I would not be returning to Finland, but instead hopefully finishing the ride in my new home in Germany. Everything had changed after Eastern Dirt 14. I had since sold my business and moved to Berlin with my much better half. The last thing left in Finland was the 690, and it too would soon sail over the Baltic with me.

Eventually the queue of bikes, most consisting of Harley Davidson’s, roared to life. The exhaust note of my 690 single cylinder drowned under the loud pipes of the V-twin engines, carrying their chubby leather-clad operators and passengers into the bowels of the ferry. I’ve always found the whole Harley scene rather comical. The stereotypes seem to carry an air of harmless threat or unfounded superiority, despite the fact that telling the men and women apart is almost impossible. Either way, we were all part of the same fraternity of riders and, exchanged polite greetings and route inquiries while strapping our bikes down to the steel deck of the ship. However, they seemed to eye my banged up adventure enduro with pity in their eyes.

The car deck was off limits during the two hour crossing, so I made my home in a quiet corner of the public area. I was very hungry, but exhaustion took the best of me and I soon drifted in and out of consciousness. The crossing was uneventful, but it was a very real divider between what was behind and what was to be. However, due to the exhaustion, I was not in the correct mindset yet. Everything still seemed….obscure.

Riding out of the ship, I was met with sunshine and the wonderful heat of summer. The city gave smooth passage, and I was soon on my eastbound track through the northern coast of Estonia. It was mostly small tarmac roads, so nothing to get excited about, but the feeling of making progress was very welcome. Unfortunately the rattle from somewhere around the front sprocket was still there, so I stopped to investigate. The chain was hitting the Rally Raid sprocket guard, probably due to a worn out chain slide, or just because the chain was brand new. Either way, the noise only occurred during engine braking, so I switched to riding the 690 like a two stroke to counter the problem.

The next pressing issue was fuel, both for the bike and myself. They were taken care of at a petrol station, and I was soon back on track towards my rendezvous with the Swedes. I’d sent them my track, and they had arrived earlier in Tallin with by a ferry from Stockholm and were ahead. I pushed on, and finally the tarmac road was replaced by a short section of dirt, spitting me to the edge of a bay. Across it, I immediately spotted two bikes, and the first attraction on The Crimson Trail; the abandoned Soviet submarine base with its derelict pier reaching out to the Hara bay. It seemed like a fitting location to rendezvous with the Swedes and dive right into the essence of the Crimson Trail; the Cold War.

The two Swedes walked up to me from the pier. Perra was an old friend from cave diving, with whom I’d shared many good dives. Underwater he was one of the most reliable and cool headed divers I’d ever met, and I was looking forward to seeing how he operated in a non-lethal environment. To be honest, I had some reservations, as he apparently currently mostly consisted of titanium. Perra loved skiing and was passionate about bikes, which he had been riding for a long time. Mostly older Japanese dirt bikes, but on this ride he was on a first generation carbureted KTM 950 Adventure. His friend Johan, whom I’d never met, was on a Yamaha Super Tenere with street tyres, which I eyed with some concern. He seemed like a nice calm fellow with a good physique.

After exchanging the usual pleasantries and receiving ten packs of the real black gold i.e. Swedish snus, or snuff, I headed out to the pier with Perra. The base was nothing too exciting, but with an interesting ambience and some old Soviet murals inside the buildings. The pier stretched out to sea and I walked to the end of it. The water was relatively calm and somewhere across it was where I had started earlier in the morning. Turning around and walking back to shore, the adventure was ahead and many things left permanently behind.

Our three bikes hummed across the flat Estonian countryside. We were still on tarmac, but after the town of Rakvere we finally hit dirt. The trail was mostly easy dual tracks and gravel roads, but it had recently rained and the ground was slippery here and there. It was easy riding on the 690 with MX tyres, but I was curious to see how the Swedes handled their big bikes, as I had never ridden with either one of them. They rode somewhat apprehensively, but both handled their heavy bikes impressively. They were clearly experienced riders, which was a relief.

Pushing further south, we were closing in on the rain clouds that had drenched the ground beneath us. I suggested we’d camp soon, to avoid getting wet, but an equally important reason for me was that I was just absolutely exhausted. I knew the next attraction on the Crimson Trail was not too far and we would probably find a good campsite there.

As the dirt road turned into concrete slabs, I knew we were getting close to the Rohu rocket base. It was of course also of Soviet origin, and had been decommissioned in 1978, falling since into decay. It wasn’t especially impressive as such, but apparently it had been equipped with R-12 missiles. They were the famous medium range ballistic missiles with thermonuclear warheads, that covered Western Europe with the nuclear threat and gave the whole world a headache during the Cuban missile crisis. The instruments of death were long gone, but the ambience was strangely quiet and eerie. The surface launch pads were overgrown with moss and grass. Empty windows of roofless brick-houses stared at us from the surrounding forest. We decided to camp there.

A small derelict road led deeper into the forest. It was not really a road, but rather an old dirt track that had been retaken by the forest during the last four decades. We were a little off from the launch pads, so the trail would probably have been a guard road on the outer defence perimeter, as there was evidence of barbed wire mounts in the trees. My suspicion was confirmed when I rode along the trail and hit a fallen concrete pole, hidden by moss. The bike and I didn’t agree on the direction we were going so we went our separate ways, both falling over in the process. We had found our campsite for the night.

As the usual hustle and bustle of setting up camp ensued, I had a flashback from our first camp in Russia during Eastern Dirt 14. A derelict road, in the middle of nowhere, overgrown and wet. Unfortunately this time food was scarce as we hadn’t done any shopping. So I dug into my emergency rations in day one of the ride, but without too many misgivings.

The evening was pleasant with hot food and good conversation. We sat there in our strange camp longer than I expected to stay awake. But when I finally crawled into my tent just after midnight, I was utterly spent. Still, one does not camp in a nuclear missile base every night, and it was mind-boggling to imagine the amount resources that were poured into preparing for a war that never happened. How seriously they took the threat of an enemy that never materialised, and how it was all just left to decay when the party was over. It was strange to camp in spot that would have been a tightly guarded military secret just forty years earlier. Having been in the same spot then, we would have most likely been interrogated, tortured and killed.

DAY 2 / A STEP INTO CHAOS

21.7.2015 / Rohu nuclear missile base – Vortsjarv / 311 km, 498 km total

The world was clear, and the cobwebs of sleep deprivation were gone. The morning was absolutely beautiful with the sun shining on a clear sky. The eerie mood of our camp in the missile base was washed away with light and the hustle and bustle of creatures of the forest going about their daily business. I suspect they had gotten up much earlier than our gang of three. Not that we were in a hurry, and either way the long sleep had been extremely refreshing. Being part of the world mentally, in a addition to physically, was most welcome.

Sleep was one thing, but nothing ever happened before coffee and it did not take long for the kettle to be on the stove. In the mean time I tinkered with my navigators. The Swedes would roll with me for a week or so, but I suspected I’d be riding into Ukraine solo. So instead of my trusty Garmin Montana, a veteran of many adventures, I now also had a brand new one for backup. The tracks were set, but I hadn’t had time to set them up properly, and went about configuring the power button double click function, as well as primary maps and tracking. The next gadgets to be configured were the two Garmin VIRB cameras I had brought along for on board video. Both the VIRB’s and the Montanas ran on the same battery type, which made power management very easy; the empty batteries from the cameras would go into the Montana’s where they’d charge off the bike’s 12V supply. So essentially the navigators turned into charging bays, and there was never a shortage of full batteries.

As we had not done any shopping the previous day, breakfast was even more meagre than dinner, but we decided to resupply on the trail and stop for an early lunch. It seemed that the first days of all expeditions were somewhat chaotic; everyone was excited to be on the move and despite the meticulous planning, simple things were easily forgotten. The luggage inside the panniers seemed to have a life of its own, and it usually took about a week for everything to find its place. Once the gear settled, living out of the panniers became second nature, and everything could be found even in darkness. Although on that morning it was a yard sale.

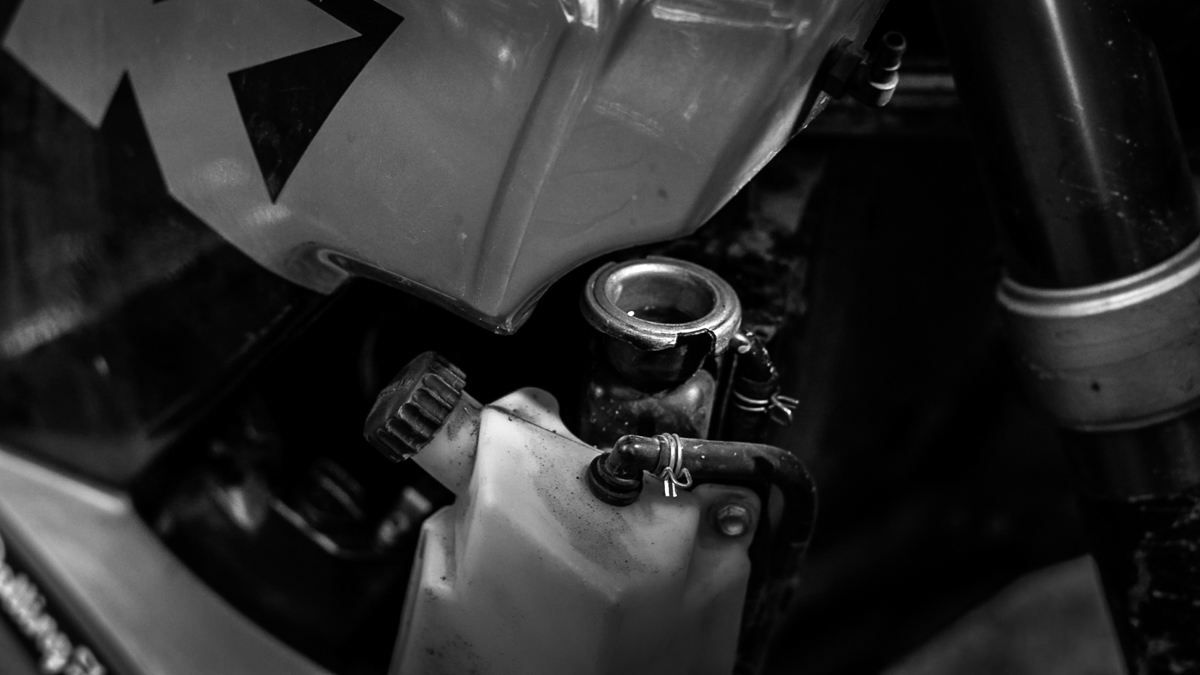

Shifty gear was one thing, but keeping a close eye on the bike during the first days was essential. As it had been taken apart before the start of the ride, I checked all bolts, fluids, chain tension and did some adjustments here and there. It was also time to lower tyre pressures as we would hopefully not see long stretches of tarmac for a long time.

Getting back on the move was a relief. Or rather, it felt like the beginning of the expedition. The terrible veil clouding my mind was gone. Instead it was a “jersey day”, with beautiful warm weather and the beginning of the Crimson Trail in great company. It was easy going, and very enjoyable. I knew there was tougher trails ahead, but most likely not in a few days. It was nice to ease into the expedition mindset, instead of being forced into it right from the start. The southbound trail ran though fields and forests on mellow gravel roads and dual tracks, before giving us the first opportunity to do some shopping in the village of Torma.

Everyone was in a good mood as we stocked up on water and provisions. I had made arrangements to meet my Estonian friend Tiit Rand. He was a veteran of several rides in Mongolia as well as the BAM road, which he had ridden solo on a Honda Transalp. I had met him during the last days of Eastern Dirt 14 the previous year. The meeting had been somewhat fuzzy, as I’d ridden 1861 km from Samara, Russia to Voru, Estonia in one 28 hour sitting. I was looking forward to catching up with him and gave him a a call to confirm our rendezvous location and time, before continuing down the trail. We stopped soon after and had a much needed picnic lunch with copious amounts of coffee. The mood was good and we spent almost an hour and a half just enjoying the food and the weather.

The route became a little trickier after lunch, and we ran into a couple of water crossings. The first one had a bridge in the form of a few planks over a creek, which was much too risky for the big bikes. Other crossings were muddy, challenging but doable for the 690. However, for the over 250 kg Super Tenere on worn street tyres it was another story. Not that the story would have differed much for the 205 kg 950 Adventure on Heidenau K60’s. Either way we ended having to double back on several occasions, which put us very far behind schedule, and I didn’t want to Tiit to have to wait for us. So the only option was to get off tour trail and fast forward on tarmac to our rendezvous in Somerpalu.

Sure enough we met Tiit in Somerpalu, and after brief introductions we proceeded to shop for provisions for the night in the town of Otepaa. On the parking lot Perra informed us of a problem with his bike. Apparently it was losing coolant. I didn’t think much of it as there was still plenty left so we decided to take a look at it later.

Stocked with plenty of food and drinks, we followed Tiit on a westbound route through wide gravel roads. As it was getting late, we didn’t have much time for sightseeing and opted instead to finish earlier to have opportunity to catch up with Tiit and have a look at Perra’s bike. Tiit led us to a beautiful campsite on the shore of Lake Vortsjarv. It was a small clearing with short grass, with views to the lake and overlooked by the remains of an ancient fort.

The lake connected to the sea via waterways, which the Vikings had exploited to pillage and burn their way across the Baltic region. I imagined how the scene may have looked like a thousand years ago, as the Viking ships had made their way up the river to the horror of anyone in their path. How the fort had likely burst into life, with soldiers preparing for the onslaught, and how peasants had fled for their lives with their meagre possessions. The scenery would have been very different with the river wider and less overgrown and the bank of the river clear of trees for a better view down the river from the fort, which itself would have hosted a garrison. But there we were sitting in peace. Our lives ending in the hands of marauding drunken Vikings was as likely as being vaporised by Soviet induced nuclear holocaust. Instead our greatest worry was a small amount of missing coolant. What a difference a thousand years make. Or forty.

Catching up with Tiit was great. He was a well travelled veteran of adventure riding and an inspiration. It was always interesting to hear stories of his exploits in the east. During his BAM road solo, he had found bear tracks all around his bike and tent in the morning. What had piqued the bear’s curiosity had been a fish stuck on Tiit’s tyre. A friendly local had given Tiit some of his catch from the river and one of the fish must have slipped out of the bag and then lodged on to the rear tyre. I didn’t even want to imagine the sensation of waking up in the middle of the night to a bear rummaging around camp. Apparently Tit had slept right through the visit.

In the meantime, Perra and Johan took apart the front fairing of the 950 to get access to the radiator. They ran the engine without the cap on the radiator which resulted in a huge plume of vapour when they shut it down and the coolant stopped circulating. Perra was clearly not happy about the situation, and made some calls to more technically versed friends for advise. When the possibility of a cracked cylinder head popped up, it struck a chord. This too was a re-enactment of Eastern Dirt 14, as during the first couple of days the Walrus had also experienced mysteriously vanishing coolant. It had of course turned out to be nothing, and I expected the case with Perra’s bike to be the same. It seemed hard to convince him though, so I suggested we keep rolling but keep an eye on it.

The transition to life on the trail affected everyone differently. It was the opposite of ordinary life, where one did not run into wild bears, camp at abandoned nuclear missile bases or wake up staring at the business end of an AK47 in the middle of the night. Riding out was a step into chaos, and attempting to control it a recipe for madness. As soon as one embraced the uncertainty, and accepted that the single controllable variable was the will to keep moving forward, the worries were over. It seemed that perfectionistic control freaks had a hard time accepting their obscure fate, especially if their glass was half empty. At least the road to improvement was rocky for me once, but adventures made us better people.

Once Perra’s bike was back together, we cooked dinner. It turned into two dinners, as everyone was hungry and the conversation excellent. I believe the Swedes were as impressed with Tiit’s adventures as I was, and he was a great source of local information in the Baltic region. He left before dusk and I finally had to get on with a job I had been dreading; my very first video diary. It was an awkward experience, and I wondered how it would look back home. Just as I finished with the video, a few drops of rain fell, and I hurried to pitch my tent in the dusk. The Swedes were still chatting over red wine, but I was done for the day. I hastily packed up my stuff and crawled into my tent. It had been a very good day and if everything went well, we should see the Latvian trails soon.

DAY 3 / AND SO IT BEGINS

22.7.2015 / Vortsjarv, Estonia – Vecaduliena, Latvia / 221 km, 719 km total.

The gusts of a stiff breeze banging on my dry tent brought be back from sleep. The short grass of the flat ground had made the night one of the most comfortable ones in memory. Even without the fatigue of gruelling days of hard off road, I had slept completely oblivious to my surroundings. The third day usually marked the beginning the final stage of transitioning into an expedition mindset. The anxiety and fatigue of the first days were over as the body started to accept the asceticism of life on the trails and camping. The mind gave up on hope and worry as it locked into the simple mission of moving forward. I always found this transition very satisfying, as the comforts and distractions of urban life lost their relevance. It was returning back to the static world at the end of an expedition, that was a struggle for me. I always found it difficult to get back to the surface at the end of it all.

However, I couldn’t have been less oblivious of the eventual end of the expedition, as I crawled out of my tent to take a look at the weather. It had turned for the worse during the night with high winds and rain in the air. Fortunately we only saw a few drops while preparing breakfast and lazing around our comfortable camp, drinking coffee. Perra was messing with his bike again and deemed everything to being back to normal. It was another flashback from the previous year’s expedition, and I was happy that we didn’t have to ride back to a KTM dealer to investigate it. It would have been a long haul back to Tartu.

Breakfast stretched for a good while, and Perra even stripped down to bathe in the lake. I hadn’t realised it earlier, but he was perhaps a little OCD on hygiene. On the other hand, I perhaps had a higher tolerance for being filthy. Wearing the same base layer until the next opportunity to take a shower in a hotel and wash the smelly polypropylene base layer in the bathroom sink was how I usually rolled.

It was close to midday as we pulled out of our camp and headed back towards our original trail. On the way we stopped briefly to refuel and Perra bought some coolant in case there were further issues with his bike. The upside of riding a big bike was clearly the load capacity, and his aluminium panniers swallowed the bottle without fuss.

Our original trail was roughly 50 km east of us and I navigated the jump on the fly. We were lucky and the route ended up being very enjoyable; small gravel roads through forests and fields. The weather also gradually improved and holes appeared in the cloud cover. The crop swayed in the wind as we rode through a world of light and shadow, stopping for photos every now and then.

We turned back south as we reconnected with the trail where we had met Tiit the previous day. The riding was pretty uneventful with some tarmac here and there, but still enjoyable small road cruising towards the Latvian border. The border crossing was smooth as expected; an empty gravel road with national signs twenty meters apart. The open borders of the European Union had their pros and cons, but to an adventure rider they were a unique luxury, which would dwindle the further south we progressed.

The border crossing had essentially been a ride over a dip on the road, but on the Latvian side everything changed. Time turned back back decades, and rural Latvia was clearly less developed than the farmlands of Estonia. It was a wonderful transition and felt as if the expedition had truly begun. The riding was absolutely fantastic as the trails snaked over steep hills and became more decayed than in Estonia. I fell in love with Latvia immediately.

As the gravel trails turned into concrete slabs and abandoned apartment buildings appeared in the forest, I knew we were getting close to the Zeltini nuclear missile base. It was one of many in Latvia, but much bigger than the one we had camped at in Estonia. I was particularly interested in this one, as I had seen photos of a statue of Lenin somewhere in the base. Unfortunately we couldn’t find the statue. It had probably been hauled away to be sold of as a Cold War memento or just destroyed.

The base was equipped with surface launch pads and we parked on one of them and took a very late lunch break in the shadow of a bunker that had held warheads not too long ago. The place was eerily quiet, but then again it always seemed like that in abandoned places. It was perhaps just the mind unaccepting the fact that a compound of that size could be void of people. Either way, there was a very post-apocalyptic vibe as we sipped coffee and ate sandwiches, while chatting in hushed voices.

After lunch, we ventured into the bunker which was mostly empty, except for some rubbish. The most interesting items ended up being some dubious looking cans, which we couldn’t figure out. Either way, the exterior was much more exciting than the inside, and we hopped back on our bikes to ride around the base. The apartment buildings had nice Soviet era murals on them, although most of them had been understandably covered up or destroyed. We spent quite a bit of time riding around the base, shooting photos, but the day was getting late and it was time to move on, as we were in need of food and stove gas.

Riding out, the gravel road soon turned into a dual track, and as we progressed, it deteriorated further. The 690 was right in its element, and by the looks of things the Swedes were rolling steady too. During the last two days I had become increasingly impressed by their skills on the behemoths. Johan especially was an inspiration, as his luggage was located high on the seat, and he was riding on street tyres. I was pretty sure that the experience of riding the bike resembled swinging a sledgehammer on ice.

As we ducked under the cover of a forest canopy, the trails became muddy and slippery. It had rained recently and the ground was soft and riddled with puddles. Checking my line, I noticed that we were no longer on any kind of a marked trail. It was just my line across an empty map. It was nothing to worry about, as I’d used satellite imagery copiously while designing the track. I typically routed my line on small trails on Basecamp with Garmin and OSM maps, and then created jumps over blank areas with the satellite imagery in Google Earth to connect the trails. It was always exciting to see if they would be ridable, and connecting the trails was one of the greater victories of adventure enduro.

The jump across the blank area was nice and flowing, but eventually the trail separated from my line. It was still going more or less in the correct heading, so I paid it no mind as the trail got increasingly muddy. I was thoroughly enjoying it, but when I stopped to wait for the guys, they didn’t show up so I rode back to see what the holdup was.

Johan’s bike was on its side in a muddy puddle and the guys were just picking it up. Fortunately Johan was clearly not hurt, which was the primary concern. He was in good spirits and we had a small discussion on the continuation of the route. I told them that higher ground was ahead and it was dryer, but that the next stage was unclear. Eventually I decided to scout the trail and come back with info, while the Swedes took a break to recover.

Riding on beyond the dry section, the trail deteriorated further with very soft sections and tricky muddy puddles that might have been challenging with the big bikes, if they missed the line. It was easy riding on the 690 with Mitas cross tyres though, and exactly the kind of terrain that I had been looking for. Unfortunately the trail had swung further away from the line, and was heading roughly 90 degrees off it. As I pushed further, the trail suddenly spat me on a large field, and three minutes later onto a wide gravel road. The connection had been made, and I just needed to convince the guys to tough it out. I always hated turning back from dead ends, but deciding to double back from a rideable trail would have been agonising. However, it would be a team decision and I would respect it, despite any misgivings.

I reconnected with the guys and gave them the naked truth. Johan was a little hesitant at first and asked a few questions on the conditions, which were duly answered. In the end I told him, that its was his call and that a decision should be made. Fortunately the proximity of the flat gravel road at the end of the trail outweighed the long return through the soggy terrain, and we pushed on. I instructed them to stop at my signal at the muddy sections, wait for me to cross them and point the line and give assistance if necessary.

In the end the jump went without incident and neither of the guys needed any assistance. Johan especially was full of confidence and nailed the lines perfectly. Popping out of the forest and onto the field, we were greeted with a beautiful scene. It was getting late in the day so the sun had sunk low and peeked over the short grass of the field, casting long shadows. It was spectacular, and the mood improved further as we hit the gravel road. Everyone was excited about having made the jump. It was a small victory, but boosted the morale of the team. Perra was a little confused though, for not seeing a trail on his navigator during the jump. I just told him that there wasn’t one, but had forgotten to tell them about it. What I didn’t tell him was that I’d deliberately left out that little detail earlier, as I had felt it might have had an unnecessary negative impact on the decision to push on. After all, it’s what’s in front of you that matters, and not what’s on the navigator.

On our way south, we stopped briefly to buy food, but had no luck with the camping gas. It was getting pretty late so we soon started to look for a campsite, which turned out to being rather elusive. I scouted a few potential trails, while the guys waited on the main track, but all trails seemed to end up being too technical for the big bikes, too close to inhabited buildings or just too wet deep forest with millions of mosquitoes. In the end we found an abandoned logging road, by which we could camp relatively comfortably and most importantly completely out of sight.

We made camp and ate a dinner of beans and sausages in the company of an army of mosquitoes. It had been an excellent day and Latvia had turned out to quite the enduro paradise, so everyone was looking forward to the next day. The evening wound on with pleasant conversation while the Swedes sipped red wine and vodka, which they’d bought during our stop to resupply. Being the sober third wheel eventually lost its charm, and I crept into my tent and soon fell asleep.

DAY 4 / dark clouds

23.7.2015 / Vecaduliena, Latvia – Kupreliškis, Lithuania / 241 km, 960 km total

The morning kicked off at a leisurely pace, and we didn’t hit the trail before around eleven in the morning. Fortunately the riding was more of the same fare we’d had from entering Latvia the previous day. The world consisted of gravel roads and dual tracks twisting and turning through fields, forests and hills. I managed to find my groove and thoroughly enjoyed the tight flowing sections of dual track, navigating through mellow pine forests. It was exciting riding, with no buffer outside of the trail, but instead just a wall of trees rigidly waiting to punish riding errors. The Swedes were in good form, and the big bikes kept up to the pace well on the non-technical terrain. And best of all, every trail connected.

Judging by the rattle of my chain, it needed some more tension and we took a small break on the trail. After sorting out the chain tension, we sat around chatting for a while and I noticed a strange vibe in the team. Per seemed very cranky and was anticipating problems with his bike. He was sure that his clutch would spill disaster on his ride, and he clearly found the lack of stove gas a huge problem too. I tried to reason with him, but to no avail. It seemed, that since the mysterious problem with his coolant had vanished, he needed something else to worry about. So I suggested we’d cut some of the trails and head directly to the closest town of Koknese for a hot meal, to which everyone agreed.

After lunch, the mood improved immediately. I suppose we’d all just been hungry and tired, to which people react differently. After all we were into our fourth consecutive day of riding and no one was ride fit yet. But we all hit the road in good spirits, despite not managing to find any camping gas in Koknese either. Out last option was a large supermarket complex outside of town, but despite having several different gas cartridges, they didn’t have the threaded canisters we needed. As we got outside, the first drops of rain on the trip landed, and the guys decided to suit up into rain gear. The weather was still warm, so I didn’t bother putting on GoreTex, instead deciding to risk it. To the great amusement of the rest of the team, Per donned a red and yellow waterproof onesie with racing checkers on it.

After three hours of sporadic rain, the weather changed right on the border between Latvia and Lithuania. The border was essentially a glorified ditch with a bridge over it and sign marking the change in states on a field.

Just as Estonia is different from Latvia, so is Lithuania. Judging by the roads, Lithuania seemed wealthier, but the villages had a distinctively Soviet feel. They reminded me a lot of Russia. Buying provisions for the night, I noted that even stores were a spitting image of their Russian counterparts; dimly lit rooms with a U shaped counter and a grumpy old lady behind it, standing guard over the beer and vodka. The Swedes found it rather exotic, especially since there was a crew of locals drinking outside the store. By the looks of things they’d probably been there for a while.

Our camp for the night was tucked behind a derelict barn, on a field basking in the evening sun. It was a nice spot, hidden from prying eyes and a light breeze kept the insects at bay while drying our gear. The sky was mostly clear and after setting up camp, we just relaxed in the warm evening sun, chatting away while the Swedes finished the rest of their wine box and vodka. It was a great finish to a fantastic day, despite the odd tension and a couple hours of rain.

DAY 5 / THE RABBIT HOLE

24.7.2015 / Kupreliškis, Lithuania – Kaunas, Lithuania / 222 km, 1182 km total

There’s nothing quite like waking up early to a sunny morning at camp. Crawling out of the tent with the first sunshine on your face, and taking in the fresh air of a new glorious day on the trails. I was anxious to get moving and was happy the Swedes were in good form, so we broke camp and rode out fairly early.

The trails were pretty good, and we made good progress in great weather. We briefly needed to stop for a little roadside maintenance, as Perra’s Zumo mount had become loose. I’ve never been a fan of the Zumo, and instead relied on the Montana, which is bomb proof on the Garmin cradle and RAM mount.

Our journey south continued on trails without incident, until we hit a short wet section churned out by forestry machinery. It was nothing exceptional, and easy riding on the 690, but the Swedes were having a hard time on it for some reason. I was expecting Johan to be suffering with his slick tyres, but to my surprise it was Perra who was pissed off about the section for some reason. As he was getting increasingly cranky, I wondered what the problem was, and opted to try the lunch diversion again. Both guys were happy with the plan and made for the town of Ukmergè.

A pizza and a beer put a smile on Perra’s face and the mood improved. Unfortunately, it soon took a turn for the worse, as Perra was suddenly getting worried about his front sprocket. To me it looked worn, but nowhere near overly so, and I figured he was making an issue out of nothing. Either way, to calm him down, I suggested we’d ride directly to the closest KTM shop in Kaunas.

The route was boring tarmac, and the issue with Perra’s continued imaginary bike problems was praying on my mind. It seemed to have spiralled out of control, and adding insult to injury was the fact that we were wasting perfect weather. Unfortunately the situation didn’t improve in Kaunas as there were no sprockets available at the local KTM, nor did they stock the chain slide I was hoping to replace.

The morning had been very nice riding, but our detour had cut off a section of there Crimson Trail I would have liked to ride. Especially since there was a surface launch site on the trail. However, I was doubtful that the Swedes would agree to roll back to the track from Kaunas to hit the trails. I was getting the feeling they might be finding my style of travel rather spartan and void of creature comforts. So I asked whether they would like to take half a day off in Kaunas. I figured a shower, a hot meal and a night out might improve the mood. They bit on the plan and and we checked into the very nice Hotel Kaunas, which also had safe parking for the bikes.

I wanted a single room for myself and a twin for the Swedes. Unfortunately the hotel was fairly full and all they could offer was a triple room. As usual, the room soon looked more like a man cave than a hotel room, with nasty smelly gear strewn around. I was working on sorting and backing up my photos while the Swedes took showers and left out to town. It was a Friday night so I expected it to get messy. The first pictures of beers and cocktails popped up on my phone fairly quickly, and I wondered whether I’d be rolling solo the next day.

While having the room to myself, I managed to get hold of my much better half on Skype. She was mountain biking in Scotland with our friends, and having a great time. Apparently the trails in Torridon and Skye were fairly technical here and there, which made the riding challenging. It was wonderful to hear her voice, and I’m sure we both wished the other one safely back home in one piece.

The Swedes staggered back to the hotel at around midnight. They were pretty loaded, and it was nice to see both of them in a good mood. They broke out a bluetooth speaker for some tunes and proceeded to empty the minibar. Unfortunately it was particularly well stocked and they were on a mission to drink all of it. It was amusing to watch the spirits, champagne, wine and beer receiving a slurred individual review as they were consumed. However, it was starting to seem probable that some of the consumed goods might re-emergence, so I suggested we should call it a night, or at least turn off the music. The Swedes wouldn’t hear of it, and instead collected the rest of the booze and took their party to the bathroom. I put on my earplugs and finally fell asleep at around four in the morning, with a huge grin on my face.

DAY 6 / THE PARTY’s OVER

25.7.2015 / Kaunas, Lithuania – Ivoškai, Lithuania / 277 km, 1459 km total

Sleep deprivation was usually the biggest contributor to feeling hungover. Or so I gathered, waking up at 0800 feeling hungover, after four hours of sleep and not drinking during the previous night. I wondered if a contributing factor could have been sharing the breathing air of two royally smashed mammals. Either way, I knew the Swedes were in for a very bad day, and I opened a window before heading down to breakfast.

Back in the room, I continued working on my laptop as the signs of life started to appear in my teammates’ bunks. They hobbled out to breakfast in the same manner they had made their entrance the previous night, but without the happy grins. After breakfast, to my amazement, Perra pulled a breathalyser from his luggage, and the Swedes took turns in checking out the damage. First of all, if you need to carry one, you have to admit you have a bit of a drinking problem. Secondly, if you have a blood alcohol of 0.22% in the morning, you clearly roll like a rock star and shouldn’t give a damn about trifle matters such as DUI. Either way, they confirmed my presumption of not being fit to ride in a while.

Especially after cutting the trail during the previous days, I had no patience for waiting around for the Swedes to clear their heads. So I suggested they’d take a day off, while I doubled back to see what we’d missed. They happily agreed, and I hastily collected my gear, and went to pack up the bike. There were no emotional goodbyes, as we’d made plans to meet in Poland the next morning. They would need to take an early start though to catch up, so if they decided to have another night out, I would not see them for the remainder of the ride. They were good company, and I certainly hoped to ride with them a couple more days. But even if they caught up, our paths would undoubtedly part on the Ukrainian border, as their heavy bikes had no business on the trails I was headed for.

The big bikes were slow on more challenging terrain, and I was already behind schedule. I had planned to travel an average of 300 km daily, and thus far we had been doing an average of 235 km per day with plenty of detours. So I figured I was around two days behind my rough schedule. Not that it was an issue, as I never planned strict schedules, and having flexibility on both routing and time was necessary on rides like these. Either way, I was happy to roll out and get moving again.

The day was scorching hot, with beautiful sunshine, and getting out of Kaunas took a good while. I was drenched in sweat, before cruising on the highway offered any relief to the blistering heat. Turning to gravel, from the main road, brought my mind back to the trail, but I felt a little off, most likely due to the short sleep and not having much to eat the previous night. I was looking for the Karmėlava missile base, located just NE of the Kaunas airport.

The base had two sections, and the western base turned out to being too elusive for me. The main trail was blocked by the airport gate, and another trail ended up in a messy bog. Wrenching my bike around and out of the messy rutted trail took a good while. It was hard work in the heat, and I was going through my hydration pack at an alarming rate. The eastern base was more co-operative, and soon found myself exploring the abandoned home of the 42nd Rocket Regiment of the 58th Rocket Division of the 50th Rocket Army of the Soviet Union.

The eastern base of Karmėlava had been active from 1964 to 1990. Apparently the 42nd Rocket Regiment was the last one with the notorious R12 Dvina’s. They were the same missiles that caused the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, and which had also been in the Voru missile base, which we explored some days earlier. The base was extensive and fascinating, with four surfaces launch pads, storage bunkers and an adjoining compound for troops. I spent a good while riding around the base, and in and out of the bunkers that housed death just 25 years ago.

Everything was in disrepair as expected, but I managed to find some murals and other Soviet artefacts. I suppose it will all be bulldozed one day, as understandably the Lithuanians do not appreciate the memorabilia of occupation with the same fascination as the odd adventure rider. But being there, I sat around in an old garage for heavy vehicles, and imagined how it had all looked in the full swing of the Cold War, and what the daily grind would have been for the Soviet soldiers stationed there. I would have very much liked to see photos of the era, if they existed. And I was sure they did, but would likely never see daylight, instead gathering dust in an archive somewhere in the heart of the Russian motherland.

Snapping out of my Cold War fantasies, I realised that I was at a crossroads of sorts. The Crimson Trail swung back to Kaunas, but there was an abandoned airfield just a few kilometres back up the trail. I had no intention of riding through Kaunas again in the blistering heat, and opted to take look at the airfield instead. Unfortunately it turned out to being far beyond derelict, and in fact in the middle of an artillery range with some fairly serious looking warning signs. Being in contact with derelict nuclear missile bases may carry the odd risk of making you glow in the dark, but a live 105 mm artillery shell will unquestionably ruin your day. Besides, I was low on food and water, and decided to circumvent the remains of the airfield.

Going around ended up being a good decision, as I soon found myself in a military zone. Apparently the road was open to the public, but it was always better to avoid military installations. Especially if you were clearly a foreigner and sporting three cameras around your neck. Luckily I made it out without incident, but ended up having to do a long stretch of tarmac to go around Kaunas.

Riding south, I was starting to feel tired. It was expected, with only four hours of sleep, but for some reason I was notoriously bad at eating anything on rides. Although energy consumption was higher than normal, my food intake would remain minimal, and eventually I always ended up feeling depleted. I was cognisant of the issue, as it had plagued me for a long time, and I remember frequently bonking out on the third day on climbing expeditions, before realising that I had eaten way too little. Still, to that day, I had made no adjustments to my food intake for countering the issue.

I briefly stopped for some lunch and resupplied my water, before finally reconnecting with the Crimson Trail. It was a relief to get off tarmac, and I cruised through beautiful agricultural landscapes, dipping in and out of forests here and there. The route worked very well, except for a short section between two lakes, where it was overgrown and hard to find. After finally finding it, the trail eventually led into a water crossing. After the scorching day, it was lovely to feel the cool water fill my boots as I passed over the flooded peninsula between the lakes.

Riding solo was a welcome change to the pace, as there was no need to look into the mirrors, wait for anyone or make compromises. However, as I was drawing close to the Polish border, the forests grew darker at the end of the sunny day. It’s probably due to having to camp alone, that I suddenly missed the company of the Swedes, and wondered what they were up to, as I scouted for a campsite. The area seemed dotted with summer houses and holidaymakers, so finding a spot for the night took some time.

I pitched my tent on the edge of a small clearing, surrounded by pines on a small hill. It was in the middle of a disused track, so I was not expecting anyone to accidentally stumble upon my camp. But the mood was a little eerie, as the forest was still, but I could hear distant conversations from all around me in the fading light. A vivid imagination is both a blessing and a curse, and in moments of solitude and exhaustion most likely the latter. That night though, sensibility prevailed, and I had a can of tuna for dinner, before turning in.

DAY 7 / WE DON’T TALK ABOUT IT

26.7.2015 / Ivoškai, Lithuania – Wólka Biszewska, Poland / 265 km, 1724 km total

The border between Lithuania and Poland was the last open border for a long while, so I wanted to cross it style. The trail I had mapped was fairly dubious, but I was anxious to get on to it early, and hastily broke camp rode out. The border was in fact a small river, and my means across it was a very dubious looking rickety plank bridge. On the Lithuanian side, the ramp leading to the bridge had partially collapsed in the middle, creating a kind of a plank ditch leading onto the bridge. I figured I could power walk the bike up the steep ramp and onto the bridge. However, half of the bridge itself had also collapsed, leaving only a narrow passage on which to roll the bike over to Poland. As I was assessing the situation, the first drops of rain fell. The wooden planks became slippery, and the risk of the bike sliding off the off-camber bridge increased significantly. But despite the steep, high banks of the river, it looked fairly shallow, so I decided to try to cross the bridge.

The first issue was getting the bike onto the bridge itself, which wasn’t exactly simple. I had surprisingly good traction on the ramp for a while, and managed to get the front wheel onto the bridge. But as I proceeded to manoeuvre the the rest of the bike onto the bridge, the rear tyre slid into the middle of the collapsed ramp and went through the planks. I tried yanking the rear tyre out, but it was properly stuck, wedged between the planks.

I removed all the luggage, to lighten the bike, before any further attempts of freeing it from the grip of the bridge. I hit the starter button, revved up and dumped the clutch in first gear. With a roar of then engine and the sound of splintering wood, the bike lurched forward, free of the clutches of the planks. Luckily I didn’t overshoot the bike all the way up to the bridge, from where it would likely have ended up in the river. Once the bike was free, I laid it on its chain side to avoid damaging the brake rotor, and dragged it down the slippery ramp. The 690 was back on its feet.

It had been hard work, and I was sweating profusely despite the rain. I was very thirsty and drank the rest of the water in my CamelBak. An empty hydration pack was usually a prelude to bigger problems, and I needed to get it refilled soon. Worse yet, there was no hope of crossing the bridge solo, so I had to swallow the bitter pill of defeat and find another way to Poland. Any hopes of finding an adventurous route over the border were gone, and I crossed to Poland on a flat gravel road. It was not quite what I had hoped for. But adventure enduro is not a discipline of certainties, except for the obligation to overcome obstacles and push forward. It was a mission, which I absolutely loved due to it’s simplicity.

Further south I reconnected with the Crimson Trail, and started looking for a village where I could rendezvous with the Swedes. According to Perra, they had taken it easy the previous night, so it seemed that we would in fact roll again as a trio. I was looking forward to seeing Perra and Johan, but also desperately needed water and food. Luckily the village of Mikaszówka had a shop, which was open despite it being Sunday.

I pulled up in front of the shop, and an old man immediately berated me for something. I took my helmet and ear plugs off to get a bearing on what his problem was. I ignored him immediately, once I figured out that his grievance was that I’d left tyre marks on the sand outside of the shop. Checking my phone, the Swedes had checked in twenty minutes earlier and were roughly an hour away from where I was. I sent them the coordinates to my location and sat down for the wait. I was very thirsty, but unfortunately didn’t have any local currency to buy water.

I heard the distinctive sound of a single cylinder four stroke, and a Honda CRF450 shot out from behind the shop and absolutely tore up the main gravel road in front. The rider had no helmet, was wearing a t-shirt, a pair of shorts and flip flops and did several passes, with a small crowd of locals cheering him on. I turned around to see what the grumpy old gentleman was making of the situation, and he looked back at me sheepishly, shrugging almost undetectably.

The rider came over for a chat, and it turned out he was a friend of the shop owner. He kindly offered me a drink, and also to exchange Euros into Polish Zlotys. It solved my problem with currency and water. It was great to get to meet some of the locals, and they were rather surprised to see foreigners there, as it was a fairly remote area of Poland, close to the border with Belarus. I handed out some stickers to my new friends, just as my Swedish ones pulled up.

It was happy reunion, and everyone agreed that lunch was the priority. Luckily the shop owner also had a restaurant, and we filled up on pierogi Ruskie and Wiener schnitzel. The meal was typical Polish hearty food, and we caught up on the previous day, before hitting the trail energised.

The trails had gotten increasingly sandy, but it was good riding and the big bikes handled the soft terrain in good style. We mostly rode on agricultural service roads between fields, which made finding a rhythm a little tricky. The trails were straight, with frequent ninety degree turns. So I’d come out of a turn and go up the gear box to fifth or sixth, cruise for a minute and then then brake and drop down to second to navigate another turn. It seemed to go on forever, and finding flow took a while, but when I got the hang of it, the trail was very enjoyable. The terrain was mostly flat, but the occasional hill crest gave sweeping views over the beautiful agricultural landscape.

The weather improved as the day progressed, and most of my gear was dry. Except for the boots of course, which usually remained wet for most of the expedition, due to water crossings, rain or sweat. The mood was great and it was absolute pleasure to ride with the guys. In fact it was a little unnerving to realise how much I’d missed their company, as my near future held several weeks of solitude, unless I found company on the road.

We made camp on the edge of a field in perfect weather, and had tuna and cheese on toast for dinner. Unfortunately we were still out of stove gas, so we had to dine without hot drinks. The mood of the team was really good and I was looking forward to pushing to the Ukrainian border with the Swedes. If the weather held, we were in for another excellent day of riding.

As the evening progressed, the Swedes told me they had had pretty grim hangovers the previous day, and didn’t go partying in the evening. To make matters worse, they had had to change rooms during the day. I’m sure packing up and hauling nasty gear around the hotel in a monster hangover must not have been pleasant. When I asked about the minibar bill, an awkward silence fell in our camp. I looked inquisitively at both Johan and Perra, while they avoided my gaze, exchanging uncomfortable glances. Eventually Johan looked straight into my eyes, and solemnly stated in his thick Swedish accent “We don’t talk about it.”

Love the moody photos… How do you set up for the self portraits? Presumably, using a small tripod and the interval timer? Each result must involve many images!

Thanks Jonathan, on this ride I did indeed use a large tripod and the interval function on the Nikon DSLR. It resulted in a ton of useless photos, and the interval was dictated by the card write speed, which was about 1-2 sec per RAW file, so hardly an optimal solution. I’ve since moved to a light mirrorless Sony A6000, mounted with a radio receiver shutter release, and triggered with a transmitter mounted on the handlebar. It works very well, and can also do bursts.

I used to roll with a full size Manfrotto aluminium tripod, but currently have a small ultralight carbon fibre Sirui.

The Lenin statue is still there, at least was in May 2016 when I visited Zeltini base. https://goo.gl/maps/ETSirNSvWJ12

Thanks Markku! Somehow we missed it….